PORTSMOUTH, OHIO — Wilford Ruark was drunk. Returning to Portsmouth from the west side at 4 a.m., Ruark abandoned his automobile and walked east along the Towpath road. That’s when he encountered deep water.

The 35-year-old man gripped the guard rail and waded into the muddy water flooding his path. He underestimated the danger and cried for help in the early morning darkness.

A ferryman and his passengers heard Ruark’s cries as their boat traveled from the foot of Market Street to the west side. They pulled Ruark from the swirling water and deposited him at the Portsmouth ferry-boat landing. He was charged with public intoxication and admitted to Portsmouth General Hospital.

Ruark would recover from his ordeal, fortunate to be alive.

On this day, whether drunk or sober, it was foolish for anyone to try to enter Portsmouth from the west, except by boat. The Towpath road, U.S. Route 52 and other roads west of the city were covered with water.

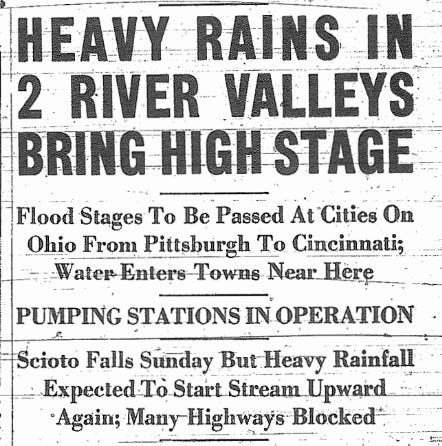

The Ohio River and its tributary, the Scioto River, bordered Portsmouth to the south and west. Both rivers were “far out of their banks,” reported The Portsmouth Times, after heavy rains soaked the area over the weekend.

Since the beginning of January, Portsmouth had seen many rainy days and little snow. On this day, the rain gauge would measure 1.35 inches of rainfall. The thermometer would climb to 50 degrees.

Rain elsewhere also contributed to the rising rivers at Portsmouth.

From Columbus, Ohio, to Portsmouth, from Pittsburgh to Huntington, West Virginia, and from Ashland, Kentucky, to Cincinnati, the clouds had dumped unusual amounts of rain in the first two and a half weeks of the new year.

The tributaries on the upper Ohio — the Alleghany, Monongahela, Muskingum, Hinton and Kanawha — were overflowing with rainwater that would eventually reach Portsmouth.

Protected by a Floodwall

Seasonal rains and flooding were as familiar as church bells on Sunday morning for this small city in the Appalachian foothills. After all, Portsmouth had a major river on its front porch and a major tributary on its side porch.

The Ohio had flooded 10 months earlier and crested at nearly 60 feet at Portsmouth. But the city stayed dry thanks to its concrete floodwall, the only such barrier along the nearly thousand-mile river. The Ohio River also reached 60.8 feet at Portsmouth in March of 1933.

Flood threats were a part of life here. The floodwall helped put the community at ease. There was a belief that major floods in Portsmouth were a thing of the past.

Nonetheless, Portsmouth officials noted the heavy rains, observed swelling creeks and rivers, and took steps to manage the situation.

Busy Pump Stations

City manager Frank Sheehan reported that pump stations were operating. Pumping began on Friday afternoon at the electric station at Lawson Run. Pump stations at Fourth and Madison streets and Mill Street began operating at 1 p.m. on Sunday and continued off and on for the next 11 hours. Both stations operated at capacity for six hours this morning.

Pump engineer Floyd Pyles said the two stations pumped more water during that stretch than any time since the 1913 disaster, the flood of record for a city that had seen a dozen major floods in a century.

Monitoring the Rivers

As the rain continued to fall, the Ohio River creeped upward at a rate of four inches per hour from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m.

On Sunday, January 10, the river stage was 28 feet. This morning, the river reached 50 feet at 8 a.m., which was flood stage at Portsmouth. At 11 a.m., the reading was 50.9 feet, and at 2 p.m., it was 51.7 feet.

City officials were also keeping a watchful eye on the Scioto River. They put in a request to the Works Progress Administration (WPA) for 100 men.

(The WPA was a New Deal program that employed millions of people in public works projects. It would be renamed the Work Projects Administration in 1939.)

The crew of 100 men would fill sandbags and help city workers place them atop the Scioto River levee. The D. Labold Company delivered 10,000 burlap sandbags to the city building. More empty sandbags arrived from Superior Cement and the Norfolk & Western Railway.

The question on the minds of officials and others:

How high would the rivers go?

Letty Hatcher

With water surrounding the city, Portsmouth residents went about their business and children reported to school.

One of those residents was Letty Hatcher. Letty lived downtown in a large brick house on the corner of 4th and Washington streets. The house was home to two families: a doctor and his wife on the ground floor and the Hatcher family on the second floor.

Letty lived with her mother, seven brothers and one sister. She was 22, the baby of the family. In a photo taken when she was 18, Letty has short brown hair, brown eyes, rosy cheeks and a bright smile.

Letty was born in Pikeville in eastern Kentucky and moved near Cincinnati, Ohio, before she was a year old. Her father farmed and sold real estate, but he became ill and died, leaving his family to grieve and consider its options.

When Letty was 10, Laskey, the oldest brother, brought the family to Portsmouth for a fresh start that depended on his new venture, a dental practice. The Hatchers stuck. They had lived in the river city a dozen years and seen two of its biggest floods.

Letty was employed by S.S. Kresge’s five and dime store on the corner of 4th and Chillicothe streets, a short walk from her home. The store was part of a growing national chain founded by Sebastian Spering Kresge of Bald Mount, Pennsylvania. It would be renamed Kmart 40 years later.

Letty would fondly reminisce about downtown Portsmouth and its shopping district.

I worked at Kresge’s dollar store. There were all kinds of stores up Chillicothe and Galia [streets] …. Martings was a beautiful store. There were lovely jewelry stores, men’s clothing stores, dry goods stores.

Those at Kresge’s on this day may have been shopping in anticipation of a flood. Or they may have been unconcerned as they moved freely on downtown streets a short distance from Portsmouth’s impressive floodwall.

Bessie Tomlin

Across town from the Hatchers, somewhere in a “colored” neighborhood as it was called at the time, Bessie Tomlin was staying with relatives, perhaps to escape her husband William, a janitor at Second Presbyterian Church on Waller Street.

Bessie’s address would soon be listed as “the rear of 1143 11th street” in the local newspaper, a short distance from the railroad tracks that crossed Waller Street above 10th Street.

From Birmingham, Alabama, Bessie was a 26-year-old mother of two young sons and an 18-month-old daughter. She was a gentle soul.

“She was a beautiful person, inside and out,” Alberta Parker said about her mother decades later. “Everybody loved her. She had a lot of friends. She was well loved.”

Nearby in downtown Portsmouth, city firemen were assigned to patrol the floodwall when the river reached 55 feet, which was all but certain according to W.C. Devereaux, senior meteorologist of the U.S. Weather Bureau in Cincinnati. At some point, the WPA was expected to send additional men to stand watch.

Seepage was already a problem.

Water came under the floodwall at Mill and Gray streets, not far from a pump station, but sandbags stopped the breach. Seepage also appeared behind the new pump station at 11th and Washington streets. Openings in the floodwall were closed at Union, Harmon and Bond streets. And sandbags would be used to fill several driveway openings along Front Street.

As the waters closed in on Portsmouth, Bessie Tomlin, mother of three, carried another baby inside of her.

Less than a mile away, Letty Hatcher carried a secret in her heart.

Read or listen to the introduction to The 1937 Flood Journal or access the archives for the full chronology and anything you’ve missed.

FRIED BOLOGNA: Family Stories from the American Midwest and Upland South Join me for stories about my ancestors who lived, worked and traveled in the hills and along the rivers of Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri and beyond.

The last two sentences are SUCH a great way to end this chapter!!