JEFFERSONVILLE, INDIANA — Six hundred miles west of the second inauguration of President Franklin Roosevelt, Chic Field skirted flooded streets on his walk home from his job at Belknap Hardware and Manufacturing Company.

“[I] had to walk around the levee and across the yard to the house,” Chic wrote in his diary.

“Around the levee” meant using the levee as an elevated walking path to avoid the rising water. The levee formed an “L” near Chic’s home. It ran parallel to the Ohio River until it reached Meigs Avenue, where it turned 90 degrees north, bordering Meigs for two blocks and ending at East Maple Street.

The water in the Fields’ basement had climbed to two feet. The water in the street in front of their house was now three feet deep. The car would have to stay in the garage as Chic wondered how to pick up his wife, who worked downtown as a dental technician for Dr. Voiers.

“Called Evelyn and told her to walk up Front Street and I would meet her.”

The rain stopped. It began falling again after suppertime.

Chic noted that the river was rising an inch and a half an hour. He walked down the street toward the pumps “to see what was going on.” The crew included men from the Public Works Administration.

“They were expecting a 10,000 gallon pump from the Quartermaster Depot and were digging a hole in the street to the sewer for the junction pipe,” Chic wrote. “The water on the inside [of the levee] was rising steadily and the rain continued. Went back home and by this time the water was on the front steps into the yard.”

The Fields’ yard and house sat four to eight steps above the level of the street and sidewalk. These incremental elevation changes were normally insignificant. But now they weighed on Chic at a moment when each additional inch of water had devastating implications.

NEW ALBANY, INDIANA — Five miles from Chic Field at 2010 East Elm Street, the Groh family was still on dry ground. But rising water was flooding homes a few blocks away.

A day earlier the family took a drive to look at the flooding in Jeffersonville, but as Marion Groh wrote in her diary, they “were not able to go more than a quarter of a mile down the Budd Road.”

Today, there were more developments in New Albany.

“A Red Cross emergency hospital was set up at the recreation hall on Third and Spring streets,” Marion wrote. “People are being taken from houses on West 8th and Spring by rowboats.”

The family was concerned about Marion’s older sister, Julia, and brother-in-law, Roger. The couple lived at 2223 Reno Avenue, a pleasant tree-lined street with modest homes on narrow lots.

“The water is several feet high on Reno Avenue and rising rapidly. Julia and Rog [have] not yet decided to move. Most neighbors are moving out, leaving but a few on Reno.”

CANNELTON, INDIANA — Seventy miles west of New Albany near a bend in the Ohio River, Mrs. Correze Cunningham gave birth to a boy in her home surrounded by flood waters. Dr. W.T. Hargis helped deliver the baby after arriving at the front steps of the isolated home in a rowboat.

Roads throughout Southern Indiana were underwater, including major routes north to Indianapolis and west and southwest toward Evansville. U.S Highway 31 was closed at Seymour. Anyone attempting to drive to Indiana’s capital from the south faced a circuitous trip.

The Evening News wrote, “Conditions in Indiana are reported as almost equal to the high mark of 1913.”

That sentence must have been incomprehensible to old-timers who never imagined the Ohio River would again rise to that level.

Guards posted near Blytheville, Arkansas, had orders to “shoot to kill” anyone who attempted to sabotage the levees.

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY — Across the river from Jeffersonville, rescue workers were evacuating families from low-lying areas.

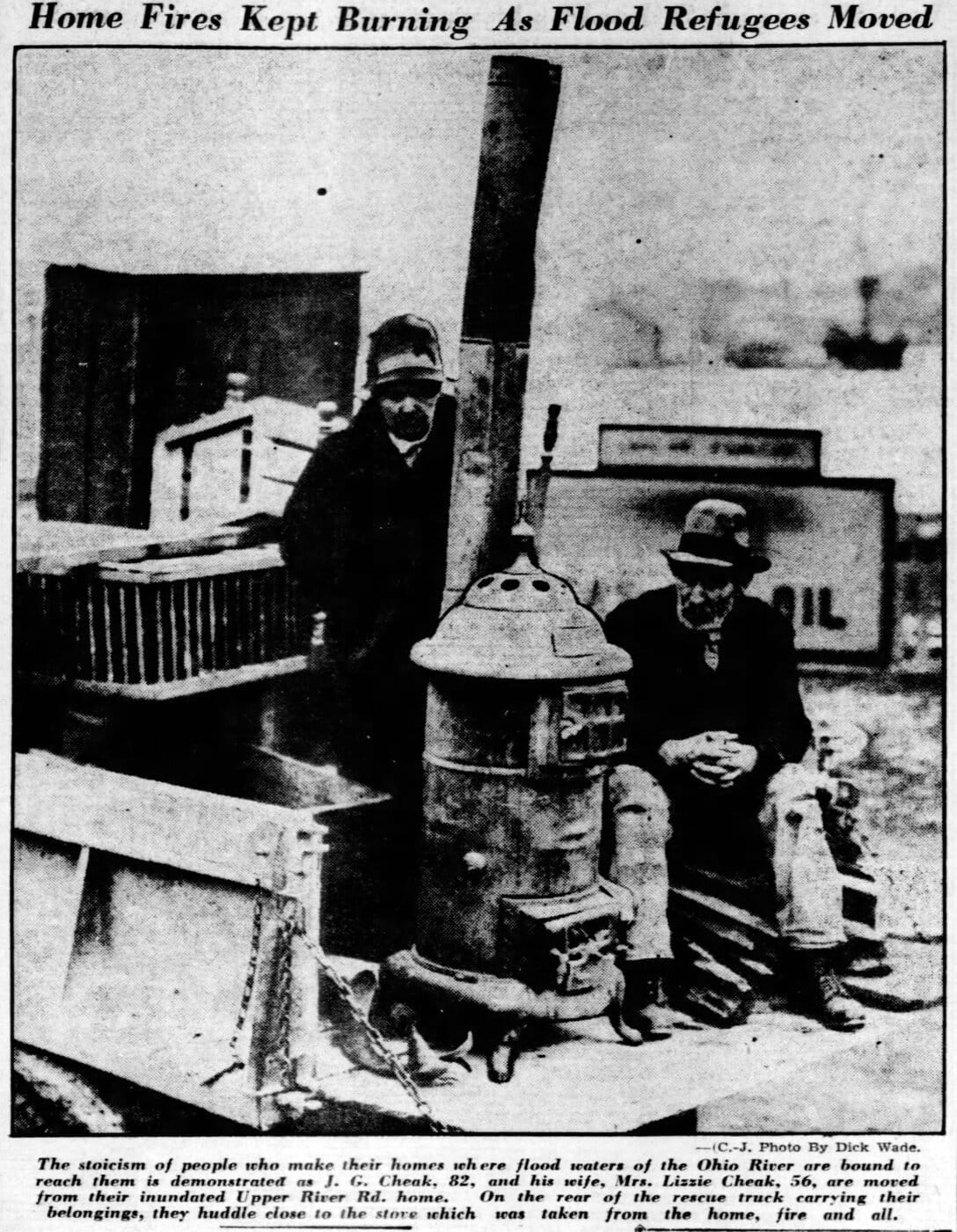

One old couple, J.G. and Lizzie Cheak, rode in the open bed of a truck with their heads down. The Cheaks were surrounded by their few possessions, including a small wood stove that was still burning. That’s how sudden their rescue was from the Upper River Road.

The Courier-Journal reported that “every stream in the state, likewise, was swollen and out of bank in hundreds of places” and “all modes of transportation and utility services were crippled.” Water covered roadways in at least a half dozen states.

In the tri-state area of Ohio, Kentucky and West Virginia, families were evacuated in Huntington, Catlettsburg, Ashland and Hanging Rock. Businesses moved goods as the water spread deeper into their districts.

In Tennessee the Cumberland River, six feet over flood stage, scattered families and encroached on buildings in downtown Nashville.

Rivers that flowed into the Ohio River from the north, such as the White and Wabash rivers in Indiana, had overflowed their banks, chasing families to higher ground.

Levees were breaking in places such as Hazelton, Indiana, on the White River, and southeastern Missouri, where nine breaks occurred along the St. Francis River. It happened despite the frantic efforts of 1,500 men working day and night for a week to reinforce the levee system.

Guards posted near Blytheville, Arkansas, had orders to “shoot to kill” anyone who attempted to sabotage the levees. As engineer J.W. Myers explained to a newspaper reporter, there are people who would go to any length to save their farms.

Ruth Richardson, 122 Walnut Street, Jeffersonville

The Richardson home was a “central headquarters for telephone calls,” said Ruth Richardson, a sophomore at Jeffersonville High School and Catherine Richardson’s daughter.

Ruth remembered an “old riverman” hanging around a nearby pumping operation and coming inside their home, a gathering place for workers and others.

“The first indication that I had that we might be in for a really serious flood came on [that] night,” Ruth said. “[The old riverman] said, ‘I have seen many floods, and I have never seen anything like this. I’ve never seen this much water. That water is coming over the levee.’”

Ruth’s father was afraid the man’s comments would scare his daughters. He took them aside and offered reassurance, saying people will predict the “very worst” in situations that create so much excitement.

“Now don’t be upset by this,” William Richardson told his daughters.

Ruth later said, “That man was the only one who had anything like the correct prediction.”

Chic Field, 510 East Market Street, Jeffersonville

Late this night Chic fretted about the situation. At 11 p.m. he picked up the phone.

“[I] called Mrs. Sagebiel, my mother-in-law, and told her that they had better get out as the backwater was [rising] 12 inches an hour and the pumps would be unable to handle it.”

Across the street at the Sagebiels, the water was within 18 inches of entering the house. Nonetheless, at that late hour, Mrs. Sagebiel told Chic they would stay put.

* * *

In Louisville, at midnight, sewers were backing up into viaducts and streetcar and automobile traffic was blocked by the water. Both here and at Jeffersonville, the Ohio River was more than 10 feet above flood stage and still climbing.

The forecast called for more rain, with a possibility of snow.

Thank you for reading. If you liked this installment, please click the 🤍. Access the archives for the full chronology of The 1937 Flood Journal.

My Family in the Story

Charles “Chic” Field, great uncle

Evelyn Sagebiel Field, great aunt

Sarah Danley Sagebiel, great grandmother