“Conditions prevailing throughout the months of October, November, and the first 3 weeks of December gave no indication of the unusual flood that was to follow.” ─Bennett Swenson, River and Flood Division, Weather Bureau, Washington D.C.

Young Ralph Sagebiel, who enjoyed sitting atop the levee in Jeffersonville, Indiana, was not the only one unable to fathom the arrival of a “thousand-year flood,” as historian David Welky called the 1937 Ohio River deluge.

People throughout the Ohio Valley were not thinking about a flood as a new year began. They had made it through another challenging year and were perhaps more hopeful for better times ahead.

After half a decade of the Great Depression, things were looking up in communities along the Ohio River and throughout the country. Business and the economy were on an upswing and families gave thanks as they gathered for the holidays and anticipated what 1937 would bring.

In Washington D.C., President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was still basking in the afterglow of a landslide victory over Kansas Governor Alfred Landon. FDR’s domestic programs were working, and the American people had rewarded him with a second term. On New Year’s Day, the president met with Admiral Cary Grayson, committee chair for the second inauguration, which was less than three weeks away.

In Portsmouth, Ohio, Henry Bannon, a former member of the U.S. House of Representatives (and who was not fond of FDR), practiced law and wrote for pleasure in his spare time. Bannon lived in a big house on the hill a safe distance and elevation from the Ohio and Scioto rivers that bordered the southern Ohio city. Letty Hatcher, a young woman who lived with her mother and older brothers at the corner of 4th and Washington streets, worked downtown at SS Kresge’s five and dime store. Bessie Tomlin, a mother of three children with another on the way, was staying with relatives in a “colored” neighborhood, as it was called at the time.

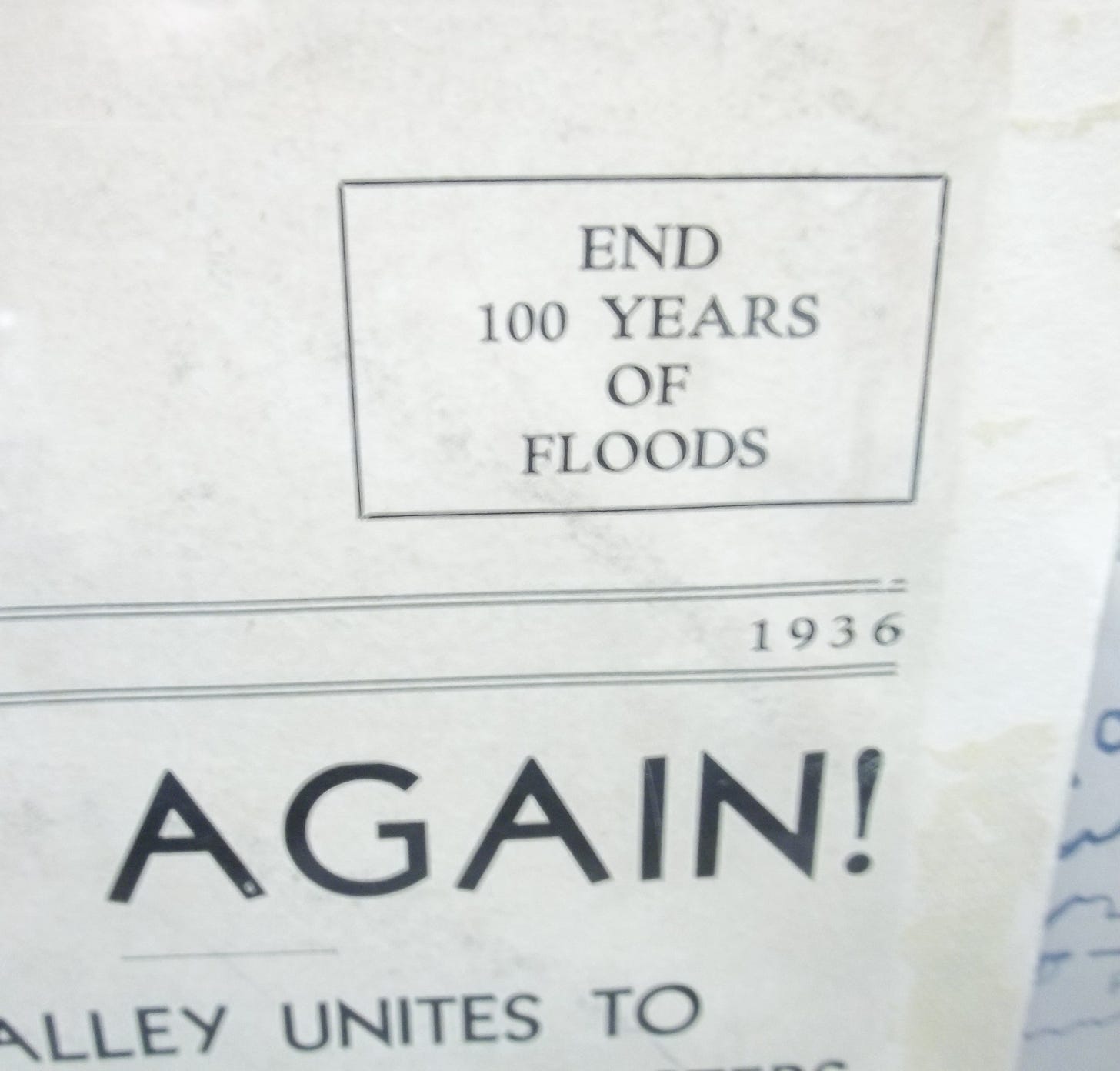

If they or anyone else in Portsmouth considered the possibility of a January flood, it was surely a fleeting thought. Portsmouth was the only city on the Ohio River protected by a floodwall. One publication said Portsmouth was “flood proof.”

W.C. Devereaux, senior meteorologist of the U.S. Weather Bureau in Cincinnati, Ohio, was going about his business of forecasting regional weather and monitoring the Ohio River. Devereaux had no clue that he would soon be working around the clock.

In Louisville, Kentucky, Mayor Neville Miller, a Democrat and staunch FDR supporter, was beginning his fourth year of leading the city known as “The Gateway to the South.” Miller could not have guessed that his enduring legacy would be summed up with the words “flood mayor.”

Across the river in Jeffersonville, Indiana, Charles “Chic” Field was enjoying a short break from his job at Belknap Hardware & Manufacturing Company in Louisville. Field and his wife Evelyn — Ralph’s uncle and aunt — lived across East Market Street from the Sagebiels. The sloping Jeffersonville levee was part of their backyard.

In nearby New Albany, Indiana, 19-year-old Marion Groh lived with her family in a small house on East Elm Street. In less than three weeks Marion would begin to keep a diary about an event she could not have imagined on New Year’s day.

Paducah, Kentucky, a river city of 30,000 people and a short distance from where the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers entered the Ohio, was a week away from seeing the first signs of a flood.

In small Ohio River towns such as Leavenworth, Indiana, and Shawneetown, Ohio, that were prone to flooding, life went on as usual. Why would anyone be thinking about a flood? Floods, if they came, came in the spring.

A new year had begun. Maybe 1937 would be a year of recovery instead of a year of misery in the Ohio Valley.

No one along the Ohio River, its tributaries or elsewhere saw the flood coming because it was nearly impossible to predict a catastrophic weather event. Weather forecasting was primitive compared to the 21st century. The technology to predict, observe and track atmospheric conditions did not exist.

But on the first day of 1937 something vast and unseen was forming high overhead. The rain was about to begin.

Start at the beginning of The 1937 Flood Journal or access the archives.

FRIED BOLOGNA: Family Stories from the American Midwest and Upland South Join me for stories about my ancestors who lived, worked and traveled in the hills and along the rivers of Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri and beyond.

I like how you’re setting up the characters I’m guessing we’ll follow throughout the flood. This is really interesting so far!

Interesting!