I’m pausing the flood narrative to share another edition of author notes, which is a look behind The 1937 Flood Journal. These notes also bring other news from my little corner of Substack: I am launching another publication, and I want you to be among the first to know. (More information below.)

* * *

In 1959 Johnny Cash released “Five Feet High and Rising,” a song about the 1937 flood that drove the Cash family from their home in Dyess, Arkansas. Johnny, called J.R. as a boy, was 4 years old during the flood. The disaster obviously had a lasting impact on the future music legend.

The song begins, “How high’s the water, Mama?” The water and Johnny’s voice continue to rise throughout the tune. Here’s another verse: “We can make it to the road in a homemade boat. That’s the only thing we got left that’ll float.”

The Cash family was threatened when levees broke along the Mississippi River. It’s noteworthy that the Great Flood of 1937 — the flood of record on the Ohio River (and my focus) — also overwhelmed the middle and lower portions of the Mighty Mississippi and its tributaries, driving hundreds of families from their homes.

By happy accident, we visited the boyhood home of Johnny Cash after Christmas on our way to see a piece of family property in the eastern Ozarks. I stood in the yard and scanned the heavy skies and puddled cotton fields that surrounded the small house.

There’s something about standing on the ground from which so many anthems bloomed, including songs about people on the margins of society and their hardships.

After our stop in the Ozarks near Hardy, Arkansas, we continued on to Cape Girardeau, Missouri, on the Mississippi River.

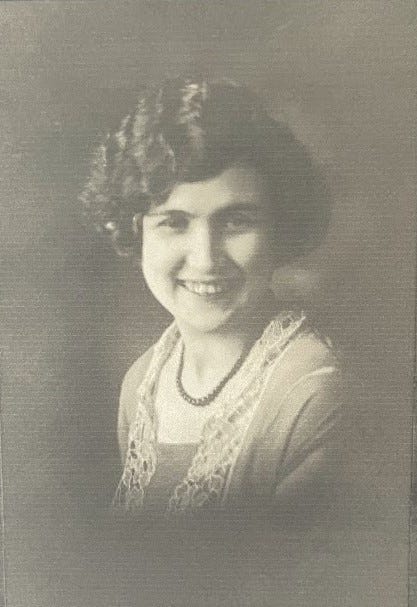

For the first time, I visited my maternal grandmother’s hometown a short distance from Cape Girardeau, formerly called Fornfelt and renamed Scott City in 1960. Her name was Florence Myrtle Moore, and I discovered new details about her early life and the life of my great grandparents, whose graves I visited in Fairmount Cemetery in Cape Girardeau.

We continued on to Noble, a small village of about 700 people in southern Illinois, and the birthplace of my maternal grandfather, Raymond Milton Moore, and his older brothers, Virgil and Clifford. Again, there’s nothing like being there — driving the roads, walking the ground and seeing the places your people inhabited.

I tell you this, in part, because I have more family stories to share, stories in now-faded manila folders that my mom quietly handed to me decades ago. I have stacks of family photos on the back of which she carefully wrote details about people named Moore, Pryor, Tolliver, Browne and Hankins. I have the family trees she made on her primitive PC, and the reports and short biographies she wrote about her parents, grandparents and other close and distant relatives.

These stories from my mom’s side are not a part of the flood narrative, and so they need their own home:

FRIED BOLOGNA: Family Stories from the American Midwest and Upland South

Please sign up today because I’d prefer not to start a continuing series until the seats are filled — or at least the front rows. I will publish a new installment every week or two.

In Fried Bologna, you will meet folks such as my great uncle, Virgil Bravard Browne, whose first-person account of his rollicking boyhood in Noble circa 1900 is one of the first series I plan to share.

Thanks again for reading.

Until next time,

Neil

P.S. If you enjoyed this, please let me know by clicking the like button, leaving a comment and sharing The 1937 Flood Journal with others. Thank you for your support.

Access the archives for the full chronology of The 1937 Flood Journal.

I love old family stories. Count me in!

Thoroughly enjoyed it.