A Saints and Sinners Guide to Jeffersonville, Indiana

Work, worship, love and gambling in the river city.

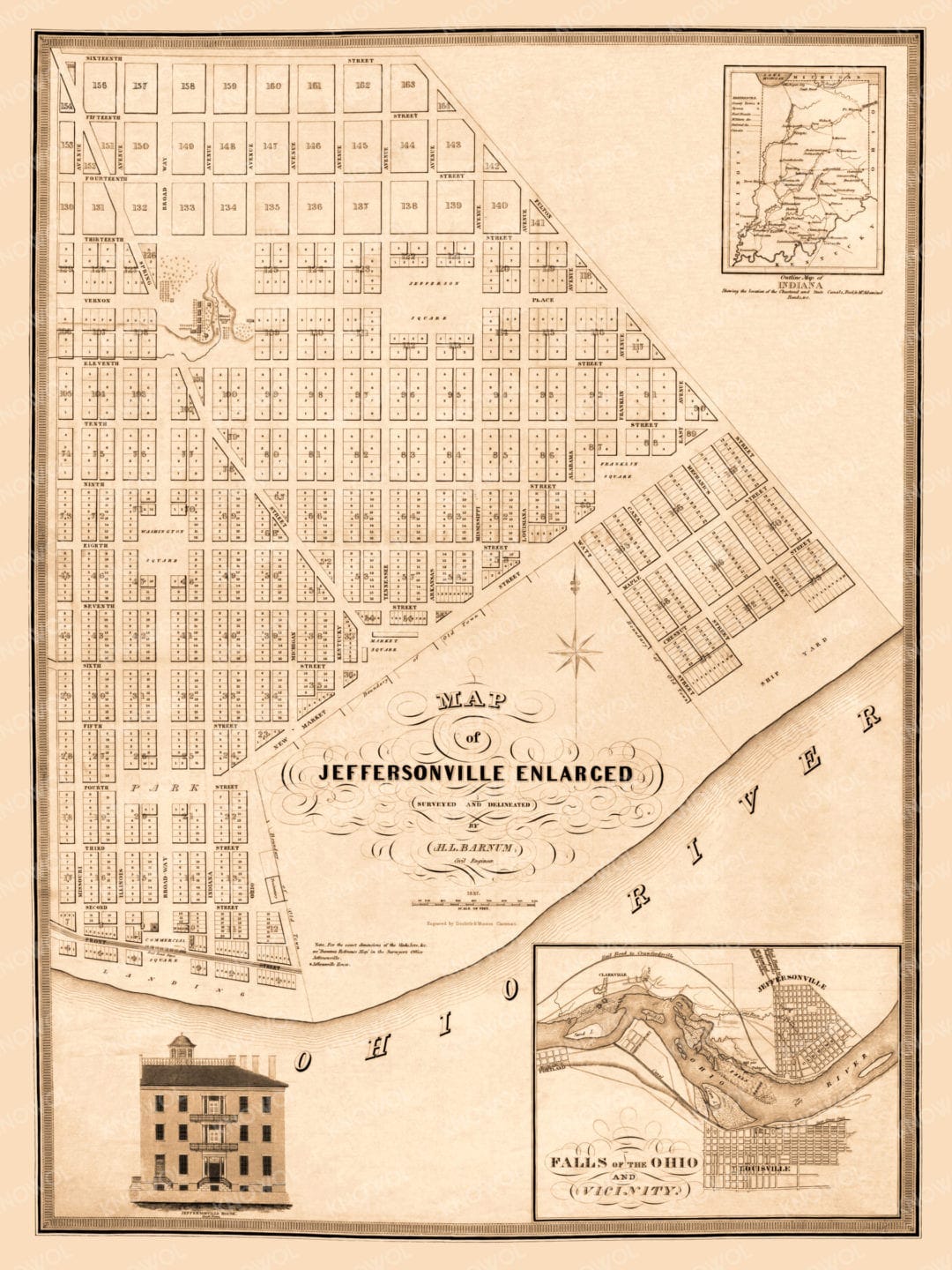

Founded in 1802, Jeffersonville was a river city. It also called itself a rail city, but its main identity was linked to the Ohio River.

Historian Garry J. Nokes wrote:

Always weaving its way through the city’s history is the Ohio River, and Jeffersonville’s attempt to profit from it, get across it, have fun on it, and, sometimes, get away from it.

This was the home of the Sagebiel family and Charles and Evelyn Field, who lived steps from the river on East Market Street, and also the home of Arthur Smith and others whose names and movements will be revealed when high waters pour into streets, houses, schools and buildings.

The junction of three railroad lines near the river made Jeffersonville a strategic spot to erect a military hospital during the Civil War. Later, inexpensive land coupled with the belief that Jeffersonville was flood-proof after the levee repelled the 1907 deluge spurred residential and business growth.

“Well-heeled residents lived in large, century-old brick homes,” wrote historian David Welky. “The less fortunate occupied riverfront shacks.”

Whether from a mansion or a shack, a river view was one of the few things rich and poor people had in common. Most Jeffersonville families earned less than a $1,000 a year.

In spite of the economic divide, Jeffersonville was a pretty good location for families and industry. By 1937 the small city of 11,000 people had experienced modest growth, even as the Great Depression disrupted commerce.

The Jeffersonville city directory touted the infrastructure during this period:

The city has a complete system of concrete and brick streets and a complete sewerage system.

In addition, new subdivisions had been platted. Water and gas mains were extended to serve the city’s new neighborhoods, such as Howard Park “with all modern conveniences.” Electricity, water and gas were furnished by the Public Service Company of Indiana.

The city was especially proud of its water, which was pumped from wells:

Jeffersonville has the best and purest water supply in Indiana.

The Quartermaster Depot

Jeffersonville was home to one of the U.S. Army’s largest depots of the Quartermaster Corps.

It began during the Civil War when a building in Jefferson General Hospital became a garment factory. Cutting garments by hand for shirts and pants, local mothers, sisters and widows were supplied four to eight bundles to assemble and return as finished goods. Later, the depot provided harnesses, saddles, hardtack and various hardware to the Union army.

The Quartermaster Depot was the country’s largest shirt factory during the Great War (later known as World War I), employing up to 8,000 civilians during the war effort. Once again with the labor of local women, the depot produced 700,000 shirts a month (or more than 8 million a year).

As of 1937, other large employers included the American Car and Foundry Company and Colgate Palmolive Peet Company with its 40-foot diameter clock, a landmark on the north side of the Ohio River. Smaller but noteworthy Jeffersonville businesses included the Fine Shirt Factory, Roberts Veneer Mill, Howard Shipyard & Dock Company, the James A. Gorsuch Foundry and the Armour Fertilizer Company.

Louisville’s ‘Wholesome’ Neighbor

Connected by rail, pedestrian and automobile bridges, Jeffersonville was a close neighbor to Louisville, the Kentucky metropolis directly across the river.

As noted in the city directory, Jeffersonville was an “ideal location for home seekers” that “affords a wonderful opportunity to people doing business in Louisville to live on the North side.” Jeffersonville also had the “best of high, ward, and parochial schools” and “beautiful churches of every denomination.”

The houses of worship were located at many intersections throughout Jeffersonville, known by some as the “City of Churches.”

Charles Field attended First Presbyterian Church at the corner of Chestnut and Walnut streets, as did Dr. Ralph Bruner, who, like Field, was married to a Sagebiel. The Sagebiels on East Market Street were not regular churchgoers, although some in the household would eventually join a Methodist church in the Port Fulton neighborhood.

Jeffersonville’s many civic organizations included the Board of Trade, Rotary Club, Lions Club, American Legion Post, Veterans of Foreign War and the Business and Professional Women’s Club.

Ultimately, city boosters proclaimed that Jeffersonville was “a clean, safe, and wholesome city in which to live.”

The Marriage Trade

Not found in the rosy pages of the city directories was another side, and some might say a dark side, of Jeffersonville.

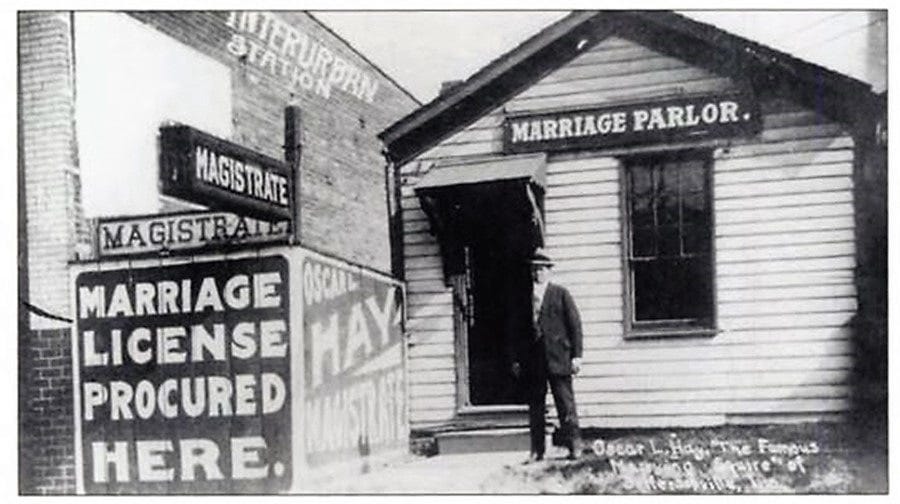

The river city was known for its marriage parlors on Court Avenue, located a short distance from the bridge. The parlors were a magnet for couples, mostly from Louisville and rural Kentucky. In Jeffersonville and Clark County, Indiana, young lovers could avoid waiting periods and residency requirements.

Enabled by lazy law enforcement, the marriage business “angered couples’ folks back home … who cursed the marriage parlors,” according to Nokes.

Called “the Marrying Squire,” Oscar L. Hay was a prominent figure in Jeffersonville’s marriage trade. The above photo shows Hay in his dark suit, tie and fedora standing in front of his marriage parlor next to the Interurban Station. His bold signage would probably earn an enthusiastic thumbs-up from Don Draper.

During the peak of the marriage business, when up to 8 in 10 marriages were couples from outside of Jeffersonville and Clark County, runners were dispatched to gather the lovebirds from trains, trolleys and ferry boats. And because hearts were not constrained by the hands on a clock, a deputy county clerk was on duty from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. to crank out marriage licenses.

The Gambling Parlors

Love brought people in droves to Jeffersonville. But so did gambling.

“The city’s illegal but nevertheless wide-open gambling parlors shocked the upright and attracted nearly everyone else,” Nokes wrote.

During its “decades of decadence,” Jeffersonville was called “Little Chicago” for what journalist Mike King called “wide-open, we-dare-you-to-close-us-down illegal gaming.”

The gambling establishments included the Antz Café, Court Café, 119 Club, 121 Club and 125 Club, all huddled along one block of West Court Avenue in downtown Jeffersonville. Their patrons could spin roulette wheels and play craps and other games of chance. Furthermore, because the parlors also operated as bookmakers, they could place bets on races throughout the United States.

It seemed that Jeffersonville had something for everybody. It would soon have something else for everybody — a winter flood that would make other floods forgettable.

Few people, if anybody at all, would have bet on that.

Read or listen to the introduction to The 1937 Flood Journal or access the archives for the full chronology and anything you’ve missed.

My Family in the Story

Charles Field, great uncle

Dr. Ralph Bruner, great uncle

The Sagebiels on East Market Street

FRIED BOLOGNA: Family Stories from the American Midwest and Upland South Join me for stories about my ancestors who lived, worked and traveled in the hills and along the rivers of Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri and beyond.

Wow! There he is—the marrying squire. I never expected to stumble upon a photograph of Oscar Hay!

I've never heard of the Quartermaster Depot. What a neat piece of history! Jeffersonville was a fascinating place in the 1930s.