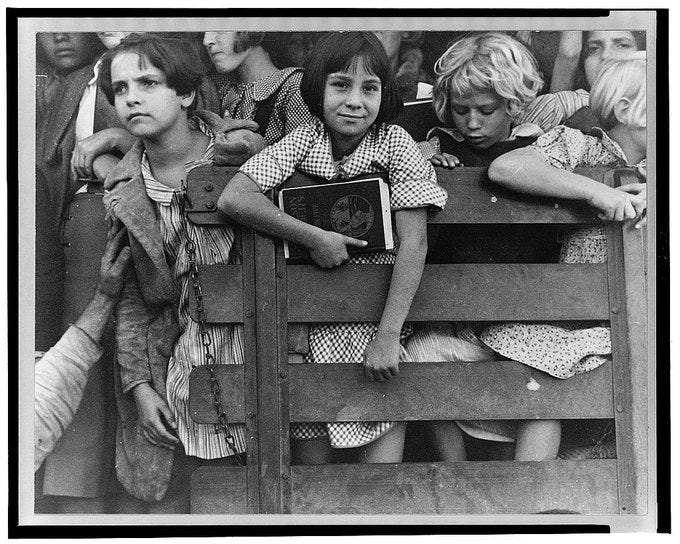

A Boy's Life in the Great Depression, Part 2

A look at 9-year-old Ralph Sagebiel and his family before the flood.

Here’s the second of two parts about the Sagebiel family before the great flood arrived in January 1937. Read Part 1.

JEFFERSONVILLE, INDIANA — The LeRose Theatre was a six-block walk from the Sagebiel home on East Market Street. Built in 1920 in the Renaissance Revival architectural style and with a seating capacity of 1,187, the LeRose was big and lavish, a thrilling experience for young moviegoers.

Especially for a boy named Ralph Sagebiel who worshiped cowboys.

Ralph’s grandmother (Sarah Danley Sagebiel) took him to the LeRose Theatre on Saturdays. Admission was a dime for children and a quarter for adults. On the way they’d stop at Schimpff’s Confectionery two doors from the movie house and buy a sack of freshly made cinnamon red hots for a nickel. The red hots would last the whole weekend.

“My grandmother was really nice,” Ralph said.

Hollywood was a bustling movie factory in the 1930’s, with millions of eager young and older fans all across America. Cowboys galloping across the LeRose screen included Tom Mix, Buck Jones, Gene Autry and William Boyd, who played Hopalong Cassidy.

But Ralph’s favorite cowboy was Ken Maynard, a good guy who wore a white cowboy hat, fancy shirts and manly scarves, and who holstered a pair of shiny six shooters in case talking failed to settle differences.

Ralph also listened to cowboy programs such as “The Lone Ranger” on the family’s RCA Victor console radio.

One Christmas he tore open packages containing a cowboy outfit and cap guns. Now he was a cowboy. What could be better?

Uncle Bill

Trips downtown included stops to see Uncle Bill working at Wendel’s, a men’s clothing store on Spring Street across from the theater. The men’s wear was top drawer, and Bill Sagebiel wore it well.

“He was sort of my idol,” Ralph said. “He was 6 foot 2, he was slim, and he dressed like a million dollars.”

A bachelor at the time, Bill had two loves besides fine clothing. One was tennis. Ralph only knew of one place to play tennis in Jeffersonville. Bill would slip into his tennis clothes, grab his racket and head out the door.

“He used to go play in the summer almost every weekend he wasn’t working.”

Bill’s other obsession was popular music.

“He loved sitting up late at night and listening to the big bands playing from New York City and Pittsburgh, where the three rivers come together.”

Bill Sagebiel would own all of Bing Crosby’s records, all of them 78 rpm discs. His favorite female singer would be Lena Horne, who, in his eyes, was the most beautiful woman in the world. Through the years Bill acquired records of all the big bands and top singers, building a vast collection that late in life would fill the basement in his small house.

Whether the candy store and a Saturday matinee or weekend tennis and Bing Crosby singing “The Moon Got in My Eyes,” these were wonderful diversions for a boy and his uncle — and for others like them who were making the best of uncertain times.

Hanging On

The Sagebiels and others living on East Market Street were hanging on to what Ralph later called a middle-class life.

“People had ordinary jobs, pretty much, but it was getting worse all the time.”

According to census reports, Ralph’s grandfather had rented the house for at least 17 years. The monthly rent was $25 in 1930, five months after the stock market crash that was a harbinger of a long national darkness.

While Adolph likely drew a pension from the Louisville and Nashville (L&N) Railroad, his adult sons could be unsteady earners. Aunt Daro contributed through her secretarial job and Uncle Bill sold men’s clothing, but Ralph’s father, Jim, was out of work.

Jim followed his father to the railroad, as did two older brothers, Bob and Roy. (At one time, Roy and his wife, Flossie, lived next door on East Market Street.)

Adolph was a master woodworker who rose to the position of foreman in the cabinet-making shop.

“They made the wood interiors of the fine passenger train cars,” Ralph said.

Adolph’s position created a path for his sons. In the 1930 census, Roy was listed as a wood machinist and Jim was called a clerk, both employed at the railroad shop. Bob also worked in the shop but would quit during the racing season at Churchill Downs because he loved the horses. He would return to his job at the L&N railroad until it disappeared.

Ralph remembered his father as a carpenter’s helper in his early days at the railroad.

“My dad was a good carpenter,” but then “times started getting bad” and “they started laying people off.”

Jim hung on — maybe because his name was Sagebiel — but the downward slide had begun.

“All he did was sweep up the shop and clean up stuff. He was like a custodian. That’s what he did — labor. And finally, they let him go from that, and he didn’t have any job.”

By the beginning of 1937, Jim Sagebiel had suffered the same fate as millions across America. Once these legions of men were cut from the payroll, it seemed impossible to get back on it, doing anything, working anywhere.

The Sagebiels did like others: They worked hard and earned what they could; they stuck together; and they were careful with their money. They were not getting ahead, but nor were they sinking.

Hambone

Meanwhile, others in Jeffersonville were barely getting by. Sometimes they knocked on the Sagebiels’ back door.

One was a black man known around town as “Hambone.”

Hambone was about 50 years old and wore overalls, a blue work shirt, work shoes and a cap. Once a week or so, he entered through the back gate and knocked on the door. When Ralph’s grandmother answered, Hambone asked for a sandwich and a cup of coffee.

“He didn’t have any money,” Ralph said. “He never hurt anybody.”

Grandmother Sallie returned a short while later. Sitting out back, Hambone ate the sandwich and drank the coffee. Then he went on his way. “Thank you, ma’am. I really appreciate it.”

It was a common occurrence — “He wasn’t the only one” — and it was both white and black folks, although black folks struggled more.

“You had lots of different people who came at different times,” Ralph said. “It wasn’t that they didn’t want to work. It was just there were no jobs, and they didn’t have anything, and they were hungry. People accepted that and would help them, at least most people I knew.”

A Segregated City

Ralph didn’t know where Hambone went or where any black person lived.

“I used to wonder, ‘Where do the black kids go to school?’” he said in his late eighties. “I still don’t know. I never saw the black kids’ school.”

Segregation in Jeffersonville, a city of 11,000 people, was a part of daily life. It was the way things were, as Ralph recalled his childhood. He noticed differences.

Black people could not sit down in a restaurant or at the counter in the drugstore.

“They could go to the hamburger place, go up to the register at the end of the counter, order something, stand there, pay, and get out,” he said.

At the drug store, “they could go in and buy medicine, but that’s all.”

The movie theater was off limits. “They couldn’t sit in the balcony. They couldn’t come in. They couldn’t go, period.”

There was one exception. “They could ride on the bus, and they didn’t have to sit in the back.”

While Ralph wondered where black kids went to school, there were no doubts about his own school a few blocks away. He could not have imagined that he would not finish fourth grade at Chestnut Street School. Nor could he have entertained the happy thought that Wilbert would no longer torment him on neighborhood sidewalks.

Like a bend in the river, everyday life in the Sagebiel family was about to take a turn.

Start at the beginning of The 1937 Flood Journal or access the archives.

My Family in the Story

Ralph Sagebiel, father

Sarah Danley Sagebiel, great grandmother

Bill Sagebiel, great uncle

Jim Sagebiel, grandfather

Daro Sagebiel, great aunt

Adolph Sagebiel, great grandfather

FRIED BOLOGNA: Family Stories from the American Midwest and Upland South Join me for stories about my ancestors who lived, worked and traveled in the hills and along the rivers of Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Missouri and beyond.